The story of Duncan Grant and Art Fund

How do works acquired for collections with Art Fund support continue to tell relevant stories? In the first of a new series, Paul McQueen discovers how works by Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant still speak to issues relating to gender and sexuality today.

A version of this article first appeared in the winter 2022 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

At any time of day in 1910, a tap might have been heard at one of the ground-floor windows of 29 Fitzroy Square in Bloomsbury, London. Duncan Grant, it announced, calling for Adrian Stephen. The maid, Maud, once remarked to Stephen’s younger sister, Virginia (the future Mrs Woolf), ‘That Mr Grant gets in everywhere.’ For this charming, talented, privileged young man, doors tended to open. An aspiring painter, influenced by European Modernists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Grant would soon establish himself among the British avant-garde, bringing non-representational colour and geometric abstraction to his canvases. During his seven-decade career, he experimented with textiles, ceramics, murals, illustration and theatre and interior design, often collaborating with Vanessa Bell (Stephen and Woolf’s elder sister) – most notably on the decoration of Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse they shared for 45 years and today a museum telling the story of the Bloomsbury Group, the loose group of artists, writers and intellectuals associated with the London neighbourhood. Since the height of Grant’s fame, in the 1930s, Art Fund has helped seven museums and galleries across the UK to collect 13 of his works, through gifts, bequests and acquisition grants.

On 1 December 1933, 85 English drawings arrived at the Cooper Gallery, in Barnsley, a gift from the art historian, educationalist and collector Michael Sadler to his hometown, made through Art Fund (then the National Art Collections Fund) and the Contemporary Art Society. Sadler arranged the collection chronologically, from 1750 to the present day, including Grant among the ‘quite moderns’, with Flowers, a watercolour on paper. ‘There is a growing interest in pictures, not least among young people at school, and some of their teachers,’ Sadler wrote to Art Fund chair Robert Witt. ‘I should like [the gallery] to have something which, in a small way, would do for young people in Barnsley what JE Taylor’s gift to the Whitworth Art Gallery did for my wife and myself.’ Between 1892 and 1912, Taylor, the owner of the Manchester Guardian (now The Guardian) gifted and bequeathed 266 British watercolours and drawings to the Whitworth, part of the University of Manchester, where, from 1903 to 1911, Sadler was professor of history and administration of education.

Sadler’s gift set a pattern for how Art Fund would help UK public collections acquire Grant’s work over the next 60 years: one or two works at a time, through larger gifts, bequests or supported acquisitions. In 1963, Still Life with Guitar and Still Life with Flowers entered the collection of Kirkcaldy Art Gallery, along with 114 other paintings in the JW Blyth acquisition; Bolton Museum and Art Gallery acquired Partridge and Grouse and Window in Toledo, in 1991, two among 251 works in the Sycamore Collection of Twentieth-Century British Prints; and in 1996 the painter Derek Hill included Landscape (1913) in his gift of 80 works for Mottisfont Abbey, where it hangs today in the morning room.

In the same year, Art Fund supported the first in a series of important acquisitions for Charleston. In his painting Self-Portrait in a Turban (c1909) Grant is about 24. ‘He’s looking very young, and he’s looking quite sexy; he’s a confident young man,’ says Darren Clarke, head of collections, exhibitions and research at Charleston. ‘It shows that formation of an artist’s self-image.’ His choice of attire, perhaps indicative of the fancy-dress parties of the period or the Bloomsbury Group’s passion for private theatricals, might make some contemporary viewers understandably uncomfortable. Born in Rothiemurchus, in the Scottish Highlands, in 1885, Grant spent his childhood in India, coming to England in 1893 for his schooling. ‘That’s some of the work we are focusing on at the moment, through looking at our collection from those different perspectives,’ says Clarke, ‘the influences that India had on his work and what he has taken from that culture and how that appears in his work – not just in very specific objects of clothing, but also in colour and temperature and form.’ The self-portrait hangs in the studio at Charleston, above Grant’s c1910 portrait of Adrian Stephen, painted around the time of their brief love affair. Just prior to the pandemic, Charleston loaned Self-Portrait to Blenheim Palace for ‘Let’s Misbehave’, an exhibition on the upper-class party culture of the 1920s.

Another loan to the Blenheim show was Portrait of Vanessa Bell (1916), painted in the year Grant, Bell and the writer David Garnett moved to Charleston. ‘It was kind of like a Duncan Grant sandwich,’ says Clarke. ‘He was in love with Vanessa Bell but also David Garnett, certainly, and they were both in love with him.’ The two men, conscientious objectors, avoided conscription by farming the land, work to which Grant was physically unsuited but to which he applied himself five-and-a-half days a week. ‘Around that period the paintings are quite small, because they were works he might want to start and finish in that very precious time he had off,’ says Clarke. Grant shows Bell in profile, beautiful and serene, using slabs of luminous colour to build up the portrait, with areas of canvas left unpainted.

Grant and Bell gifted the work to Mabel Selwood, nurse to Bell’s two sons, Julian and Quentin Bell, when she left their service to get married, in 1918. Decades later, Selwood’s children, tidying their mother’s home as she prepared to move into care, found the canvas rolled up in a drawer. They offered it on loan to Charleston, in 1991, and it was restored, relined and hung in a spare bedroom that had once belonged to the boys. When the owners decided to sell, it was considered too precious to lose. ‘We rely on the support of [organisations] such as Art Fund to keep Charleston and its collections intact and on display to the public,’ Eleanor Crawforth, Charleston’s then head of development and enterprises, wrote in a letter of thanks, following its acquisition, in 2016. ‘Without your support we simply couldn’t do what we do.’ Following restoration work to the boys’ old bedroom, it was rehung this summer.

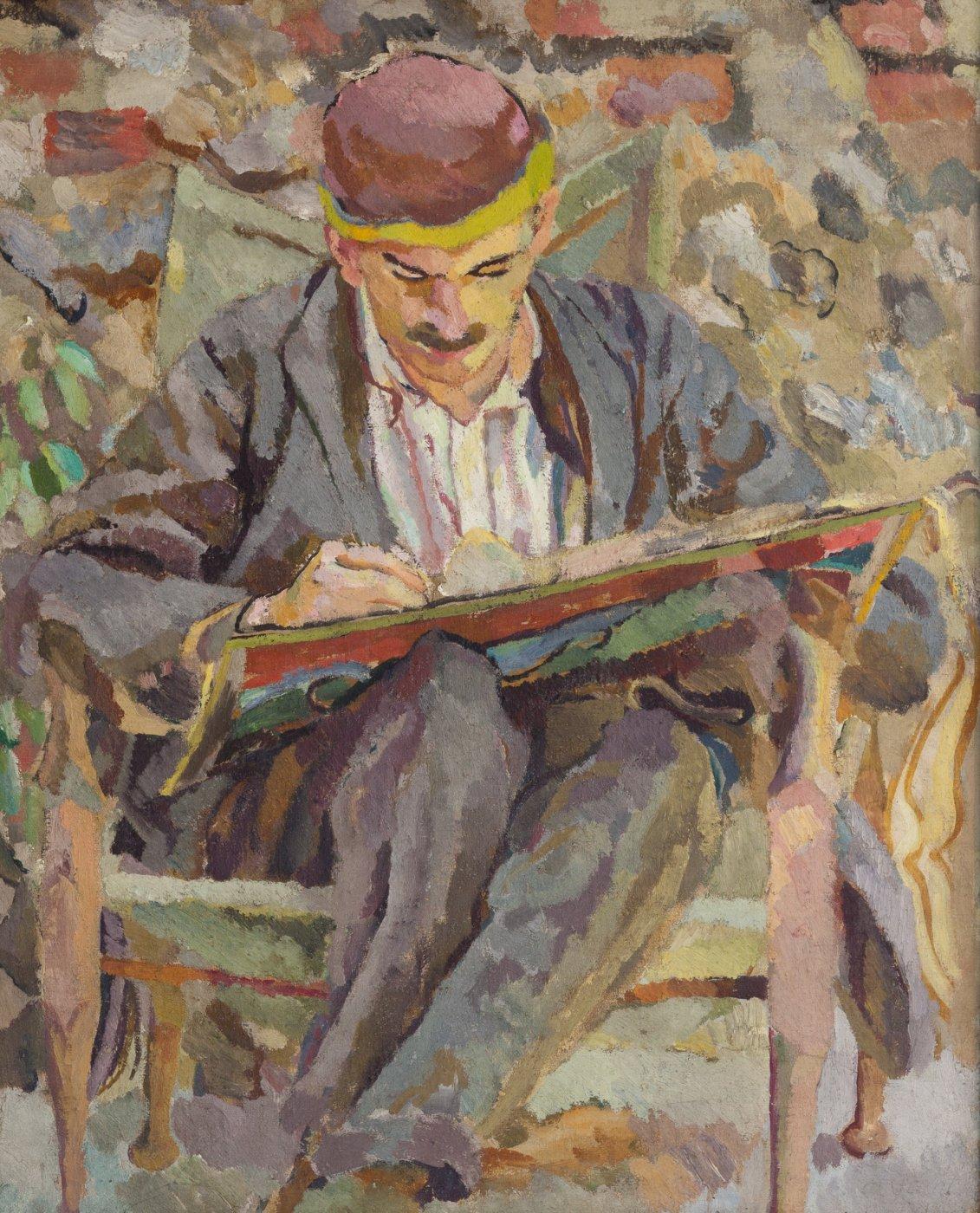

The influential economist John Maynard Keynes frequently occupied another spare room at Charleston. Keynes and Grant had been lovers, in 1909, and became lifelong friends. Here Keynes wrote his bestselling book The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), in which he criticises the Allies’ treatment of Germany after the First World War. A public figure, Keynes was often photographed, but rarely painted. In Grant’s 1917 portrait he sits in the garden at Charleston, in a low-slung chair, a flint wall behind, hard at work on a piece of writing (purportedly a telegram to the US, requesting continued financial assistance for Britain’s war effort), a purple and yellow cap from the Omega Workshops, the design collective run by Grant, Bell and artist and critic Roger Fry, between 1913 and 1919, on his head. ‘We could have had a photo of him, but the painting has much more of a presence; it feels like he is there in the room,’ says Clarke. ‘The time it took Grant to paint that picture is there on the canvas, in the same way that relationships build up over the years with brushstrokes, of time and love that’s spent together.’ Acquired with Art Fund support, in 2005, the painting introduces visitors to a man who cuts an unlikely figure in the Bloomsbury Group, most often associated with art and literature, but also prompts discussion of Grant and Keynes’ sexual relationship and the broader society in which they lived.

Grant was born some six months before the Labouchere Amendment passed, criminalising sexual acts between men. It was used to convict, among many others, Oscar Wilde, in 1895, and to sentence him to two years of hard labour, and Alan Turing, in 1952, who opted for chemical castration over imprisonment. Grant died in 1978, so he witnessed the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 and the UK’s first Pride march, on 1 July 1972. He had many relationships with men he loved, whom he often painted; however, he spent most of his life with the threat of persecution enshrined in law.

Portrait of John Maynard Keynes featured in the 2019 Charleston exhibition ‘Post-Impressionist Living: The Omega Workshops’ and, in September 2021, went on loan to the Philip Mould Gallery for ‘Charleston: The Bloomsbury Muse’. ‘John Maynard Keynes’ face is in rapt attention to what he’s writing,’ Mould has said. ‘Around him, in that sort of fragmentary Cubist way, Duncan Grant has almost amplified the thought process that’s going on in this great man’s mind; it’s almost as if all of his ideas and thoughts have become airborne.’

In 1932, art historian, museum director and broadcaster Kenneth Clark commissioned a dinner service from Grant and Bell. Over the next two years, they produced a collection featuring portraits of 48 women, from history and contemporary times, divided into four categories – Women of Letters, Queens, Beauties, and Dancers and Actresses – among them Greta Garbo, Dante’s Beatrice, Elizabeth I and Virginia Woolf. The final two plates in the Famous Women Dinner Service depict Bell and Grant. Many of the women they celebrate led unconventional lives, defying tradition in pursuit of individual freedom, and while Grant and Bell did not make the service with a feminist agenda, it can be viewed as a significant proto-feminist work, demonstrating their understanding of gender equality and the importance of making visible female stories, so often untold or suppressed.

Clark’s second wife, fashion designer Nolwen de Janzé-Rice, inherited the service on his death, in 1983, and when she died, six years later, it was sold, in Europe, and disappeared, only resurfacing in 2017, when its new owners saw a prototype plate in the ‘Vanessa Bell’ exhibition at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery. The following year, Charleston acquired what is arguably Grant and Bell’s most ambitious collaborative work, for nearly £600,000, supported by a £150,000 grant from Art Fund. It first went on display in 2018, alongside two interlinked exhibitions. ‘Orlando at the Present Time’ invited contemporary artists to respond to Woolf’s trans novel, Orlando: A Biography, published 90 years previously, and in ‘Zanele Muholi: Faces and Phases’ the South African artist presented black-and-white photographic portraits from their series documenting Black lesbian and transgender lives. Today the service is on view in the welcome room at Charleston. ‘It’s part of our collection now; we have it forever,’ says Clarke. ‘It’s exciting, what we can do with it in the future.’

Charleston’s new exhibition, ‘Very Private?’, is further proof of how works by past generations of artists continue to speak loudly to the present. On 2 May 1959, Grant left his friend the artist and collector Edward le Bas a folder marked ‘These drawings are very private.’ Inside, Le Bas found 422 erotic illustrations, made during the 1940s and 1950s, showing queer sexual encounters between models of multiple races. It was thought Le Bas’ family had destroyed them after his death, in 1966, but they survived, passing down from friend to friend, lover to lover, until they reached theatre designer Norman Coates.

In late 2020, Coates, realising both that Charleston was at risk financially due to pandemic-enforced closures and the works’ potential appeal, gifted them to the museum. The acquisition featured prominently in Charleston’s successful campaign to raise £160,000 through Art Fund’s crowdfunding platform, Art Happens, to ensure its reopening in spring 2021. Approximately 40 of the drawings will be displayed alongside responses from six contemporary artists and photographers – Somaya Critchlow, Harold Offeh, Kadie Salmon, Tim Walker, Alison Wilding and Ajamu X – exploring themes of sex, intimacy, gender and identity, and a Linder Sterling installation will occupy a neighbouring gallery. ‘We’re taking Duncan Grant’s work and then adding different voices to the exhibition space, so it’s not just this white, cis-male artist’s voice,’ says Clarke. ‘It’s taking on different approaches, different, fresh ideas, and showing how contemporary Grant’s work is, but also exploring how we can look at it from a contemporary perspective.’

Charleston’s collecting policy seeks these alternative ways of thinking in important works of art. ‘When we acquire an object, it needs to fulfil that role, to add to the understanding and appreciation of Bloomsbury, but also to visitors’ enjoyment of the place,’ says Clarke. ‘Charleston shouldn’t be seen as this historic space that you’re coming to, to be in the past; I think it has as much to say about the present. You should feel you’re also going to learn about different ways of living, and about different things that could improve your life and change your life.’ The works by Grant that Art Fund has helped Charleston to acquire certainly fulfil that brief. ‘We are custodians of those works. To make sure they are seen and appreciated, and explored and valued by other people as well, is exciting and very positive for the organisation.’

‘Very Private?’ is on at Charleston, near Firle, Lewes, to 12 March 2023. 50% off with National Art Pass.