Nalini Malani on fighting injustice with art

The inaugural recipient of the National Gallery Contemporary Fellowship with Art Fund talks lockdown, the politics of art and her installation at Whitechapel Gallery.

Who is Nalini Malani?

Nalini Malani was born in British India in 1946 (the year before Partition) and graduated from the Sir JJ School of Art in 1969, after which she worked with experimental Vision Exchange Workshop, in Bombay (Mumbai). Her early work included short films such as Still Life and Onanism, which – daringly for the time – addressed female sexuality. In 1970, a scholarship took her to Paris, where her political convictions chimed with the revolutionary mood that lingered after the May 1968 protests. She worked with illegal immigrants, distributed copies of La Cause du Peuple (a newspaper of the working-class left), and attended lectures by influential intellectuals. After two years she returned to India ‘to become part of the ongoing process of nation building’.

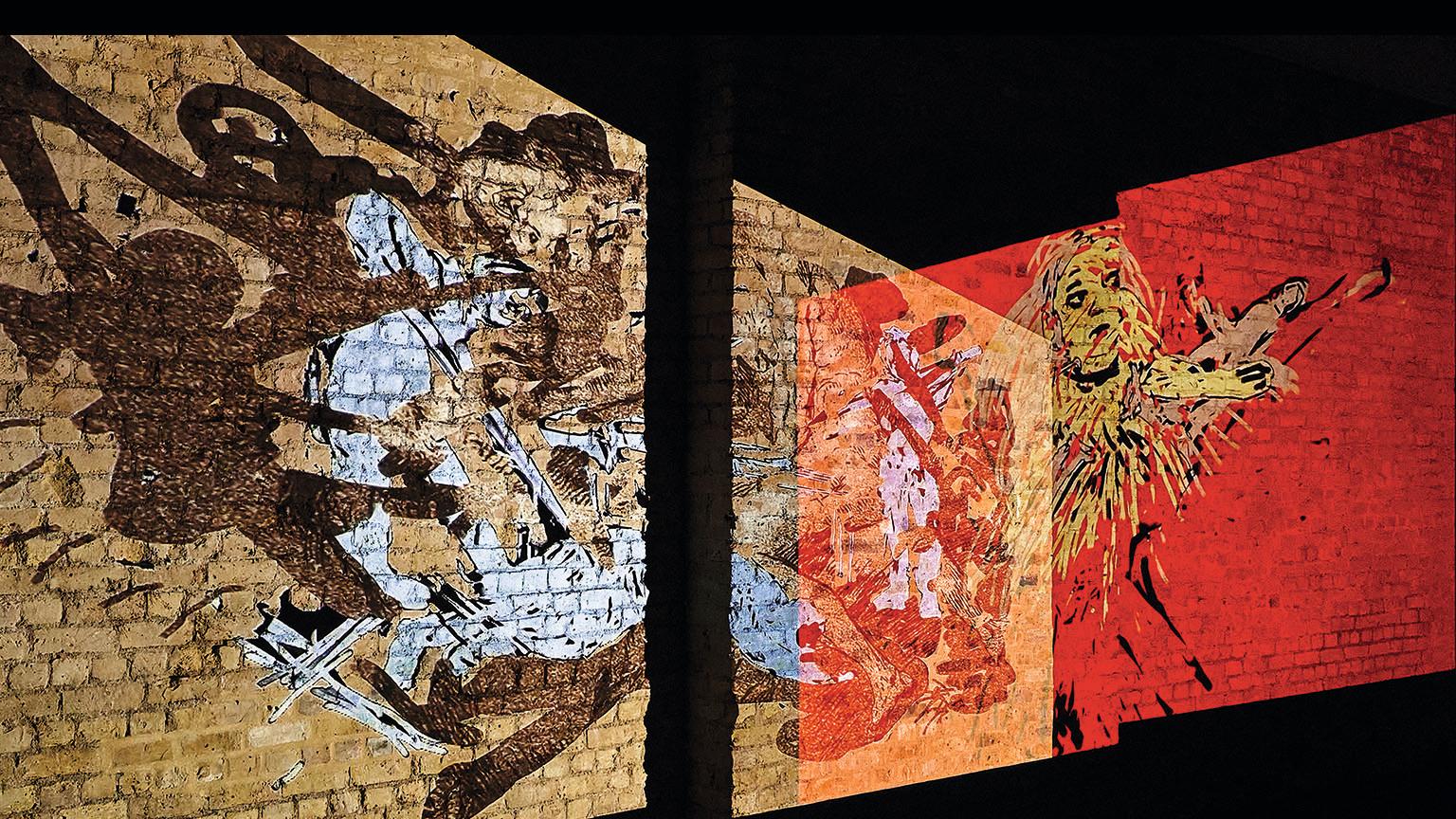

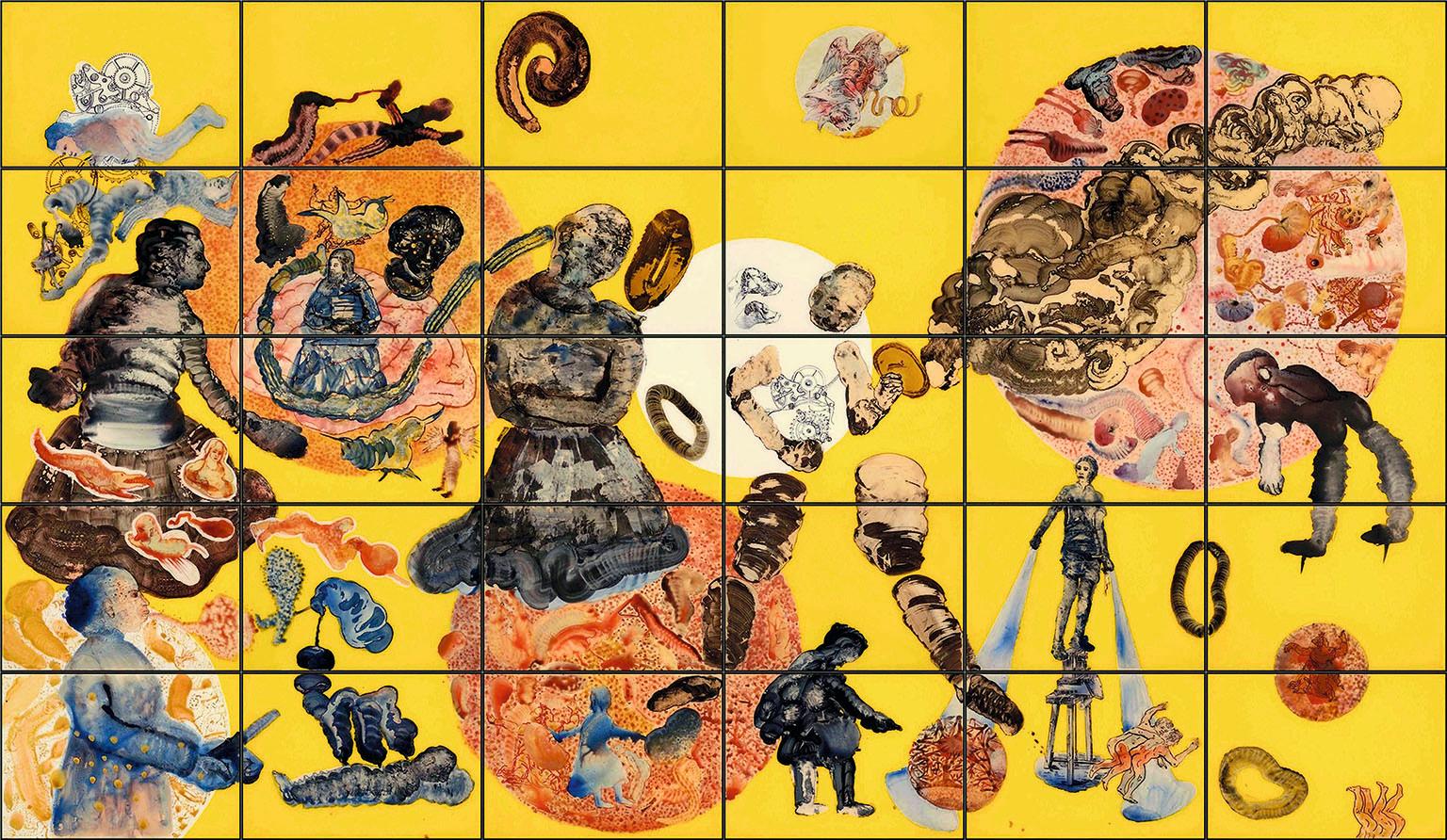

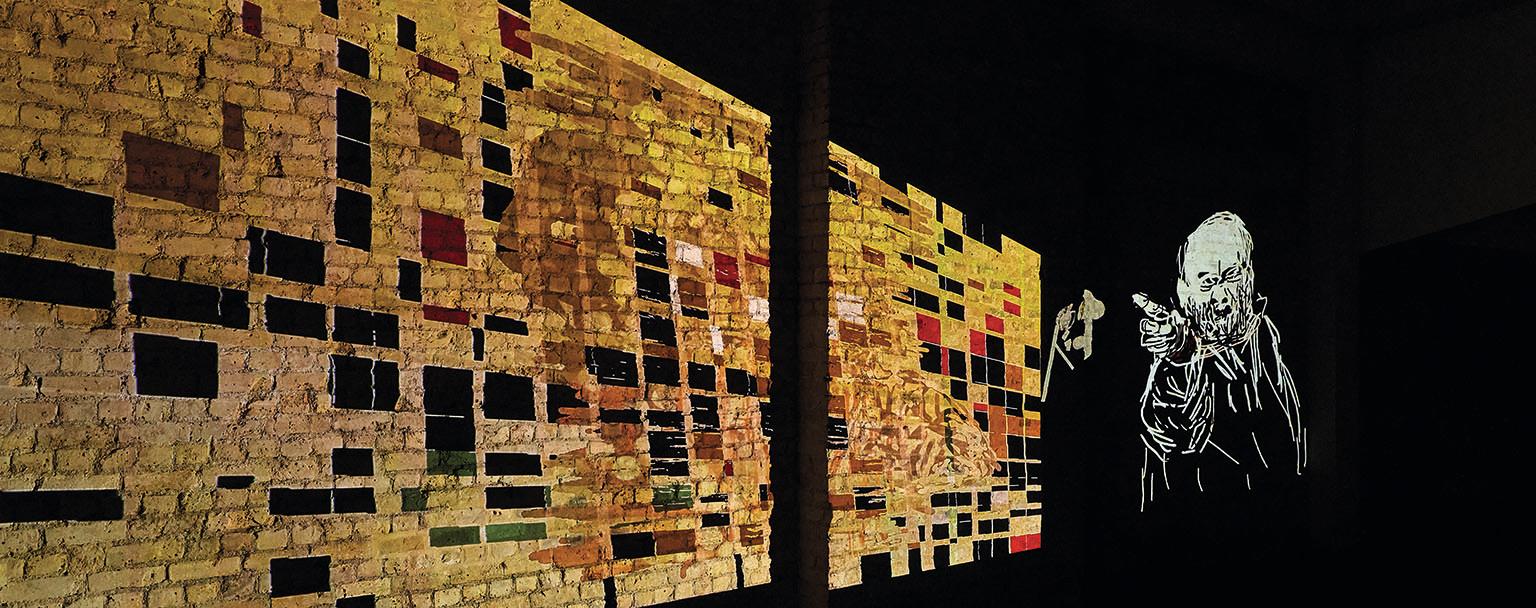

Over five decades, Malani has worked across diverse media, informed both by her politics and the enduring relevance of classical Greek and Hindu myths. In 1992, at the Gallery Chemould in Bombay (Mumbai), she started her ongoing Wall Drawing/Erasure Performances, resisting the convention of an artwork as a saleable commodity. The walls of a gallery became the canvas for an immersive charcoal-drawn environment that was later erased. This improvisatory process led Malani back to working with drawn animation. Several years later, a painted transparent cylinder she had made for an experimental staging of a Bertolt Brecht story led Malani to create intricate shadow-theatre environments, painted on Mylar plastic film.

She is the inaugural recipient of the National Gallery Contemporary Fellowship with Art Fund. Work produced during the fellowship will be shown at the Holburne Museum in Bath in 2022 and then at the National Gallery in London in 2023. Following major exhibitions at Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona; Castello di Rivoli, Turin; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and the ICA, Boston, a new installation of Malani’s projected journal-like animations Can You Hear Me? was shown at the Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Nalini Malani in coversation with Hettie Judah

Hettie Judah: In Can You Hear Me? fast-moving image, text and sound come from every direction. It feels like being inside your mind. Do you think of the short animations that make up the work as journals or diary entries?

Nalini Malani: Indeed, it started as a form of notebook. The animations are like thought bubbles: what one is experiencing outside in the world and also internally. To give an example of what triggers these notebook animations: on the evening of 24 March the Indian Prime Minister announced, amid the mounting concerns over the novel coronavirus pandemic, that, with four hours’ notice, at midnight, a nationwide lockdown would be effective. As a result, millions of migrant workers in the major cities became jobless within days, and in a massive exodus were forced to walk home to their towns, often hundreds of miles away. It was heartbreaking. It took them days, sometimes without any succour; people were walking without shoes, with children on their backs. In the animation chamber Can You Hear Me? 88 of these thought bubbles come together in a cacophony, each with their noise and voices. In many of them I use quotes from different writers – not of Indian, but of Western or Far East writers: a way of trying to avoid censorship.

HJ: There’s a quote you give from Brecht: ‘The worst illiterate is the political illiterate.’ Do you feel, as an artist, that you have a duty to step up and participate in this political discourse?

NM: It’s not a moral thing, like a duty, but there’s so much injustice that you have to speak out; it comes from the heart. These kinds of hierarchy are things that one has to address – not only in India, as you see this just as much in the Western world.

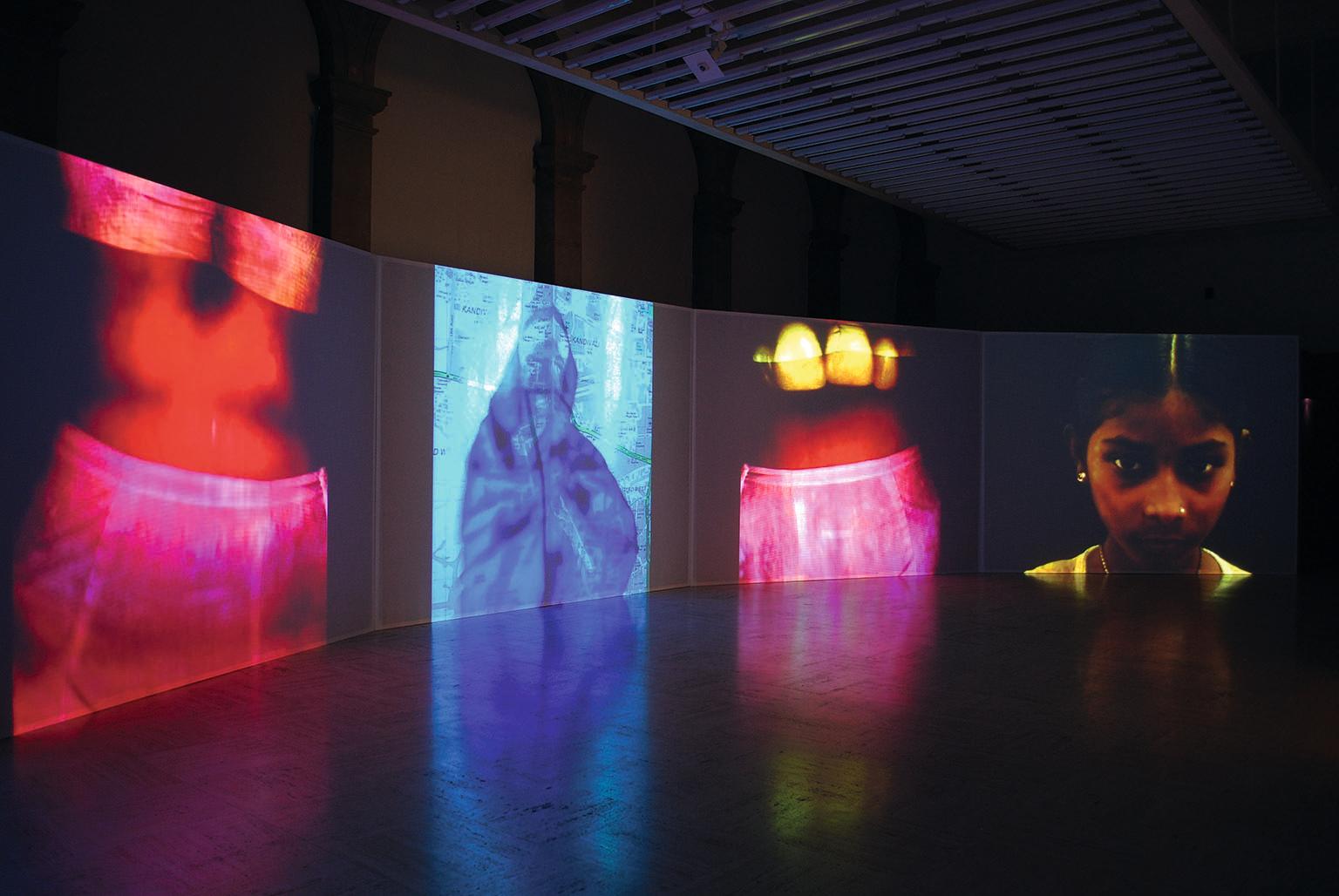

HJ: You often use theatrical mise en scène. I’m thinking of the video work Mother India: Transactions in the Construction of Pain of 2005, with the screens arranged in a big semicircle, and of your shadow lantern works. You have worked with theatre in the past: did this change the way you present your artwork?

NM: Yes, I like an environment where you walk in and it is all-encompassing and immersive. Theatre gave me the experience of memory, because in theatre, you can’t go back: you take away the memory of the performance. After working with actors and theatre directors, especially in the 1990s, I found other ways. Besides my video and shadow plays, wall drawings became one, where the drawings are erased in a performative act on the last day of the exhibition. At Castello di Rivoli, these were erased by a large group of young students with peacock feathers, and in the Pompidou by the museum team that worked on the exhibition, each with a bouquet of roses.

HJ: The theatrical references in Can You Hear Me? are great works of Modernist literature: Waiting For Godot and Endgame by Samuel Beckett, the Ubu plays by Alfred Jarry.

NM: Modernism in India has somewhat failed. We didn’t finish the whole agenda for many reasons. Just after independence, Nehru invited Le Corbusier to make the city of Chandigarh, and that was very important for young architects in India. Modernism brought about the idea of individualisation – and that comes from the Enlightenment, actually. What does that really mean for the colonised areas of the world? What was the Enlightenment and what was Modernism proclaimed by thinkers in the West? They didn’t apply that to the colonised parts of the world. So, in some sense, it was thwarted. However much colonised people might have wanted to stride ahead with Modernism, it came too late and we jumped into Postmodernism – therefore my need to stress some Modernism, because that agenda still has a lot of potential.

Language is being used in very perverse ways in the media, politics and advertising

HJ: Can you tell me about the incident that the title Can You Hear Me? comes from?

NM: This particular case was an eight-year-old child who belonged to a nomadic community of Muslims. She was caught by eight grown men, put into a temple, and over four days drugged and raped. In the end, they strangled her and killed her with a rock. It’s as if it’s malevolent masculinity. There are almost a hundred rapes registered in India per day, but the real figures must be significantly more. I want to give a voice to the voiceless human tragedy.

HJ: The mythic figure of Cassandra is very important in your work. Why?

NM: Cassandra could apprehend the future, and I think we all have a Cassandra in us. She embodies instinctive intuitive knowledge. She is the female part of us, that men and women both have, but we have to listen to it.

HJ: Of course, Cassandra’s tragedy was that she could tell the future, but nobody believed her.

NM: This is exactly what’s happening today. Think about ecology, for instance. We know what’s happening with the heating of the Earth. Cassandra doesn’t have to be here on Earth to tell us this. But nothing’s being implemented.

HJ: There are two characters that recur in your recent animations. One is Alice, from Alice in Wonderland, skipping. What’s her role?

NM: Alice has been in my art for at least three decades. It’s almost like Lewis Carroll understood dual-personality and paranoia, but he put it in different words: ‘I can’t go back to yesterday because I was a different person then.’ Humpty Dumpty says to her, ‘When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean.’ There’s a lot in these texts that is important today, where words don’t have exactitude any more. Language is being used in very perverse ways in the media, politics and advertising. Alice, therefore, is also the little girl who is the victim. In Kashmir, in one particular case, an innocent little girl strayed into an area of conflict and was accidentally shot by the police with pellet guns. In the animation you see her skipping and suddenly the pellets penetrate her whole body, almost like Saint Sebastian. Instead of announcing peace the riot police bring mayhem. For years now in Kashmir young protesting people are being shot with pellets in their faces and are losing their eyes.

There are many important parallels in Greek and Hindu myths, which link our cultures

HJ: The other recurring image you use is the screaming face of Medea.

NM: She appears, like a chorus, in all the animations from time to time, with a wide-open mouth shouting, where she embodies that furious, angry woman who has been betrayed. With actress Alaknanda Samarth in 1993 we reworked Medeamaterial, Heiner Müller’s version of Medea. This mythological story also compares with the Indian myth of Sita, where her husband, Rama, betrays Sita by wanting to test her. There are many important parallels in Greek and Hindu myths, which link our cultures for thousands of years. I discussed this often with my old friend [the late art critic and scholar] Thomas McEvilley, who did a very deep study on the comparison of these myths and stories in his magnum opus The Shape of Ancient Thought.

HJ: You have referred to Paul Klee’s description of a drawing as ‘taking a line for a walk’. I feel that you have a library of artworks in your memory.

NM: Yes, I’m very interested in the history of the line, what line can do, as a large part of my life has gone into studies on visual culture. These inspirations become ‘quotes’ which are annotations in my art. It could be a cartoon today and a classical figure tomorrow. It is what is historically pertinent for me at that moment.

HJ: Has drawing always been important? You worked in film at the beginning of your career.

NM: Yes, it has. Even with the short films of 1969, I would draw storyboards. I didn’t have so much money for film stock. So I had to be very precise about a shooting plan.

HJ: When did you start using an iPad?

NM: In 2016. I also got myself a [digital] pencil as well, but the lines didn’t feel organic enough. So I use my fingers directly on the screen. It’s like going back to finger-painting!

HJ: How did you feel about being offered the National Gallery Contemporary Fellowship with Art Fund?

NM: I was thrilled, but I was also apprehensive: I’m not an academic. And it’s more complex as the Holburne Museum in Bath is also involved in this project, which is another unique museum. But after much thought, I said yes.

HJ: Will works in the National Gallery form the basis of the Holburne exhibition?

NM: When Covid-19 allows me to travel again, I’d like to start by studying the National Gallery pieces I’ve learned from, like work by Sassetta and Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ. I can also choose something else altogether. For a long time Hogarth’s prints have interested me. They are so revealing about London in that period; there are many things that correspond with cities like Bombay [Mumbai] and Calcutta. They still give us a much-needed mirror to reflect who we are and where we might go.

A version of this article first appeared in the winter 2020 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

‘Nalini Malani: Can you Hear Me?’ was shown at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 2021.

A writer, curator – most recently of ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’, a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition – and co-founder of the Art Working Parents Alliance.