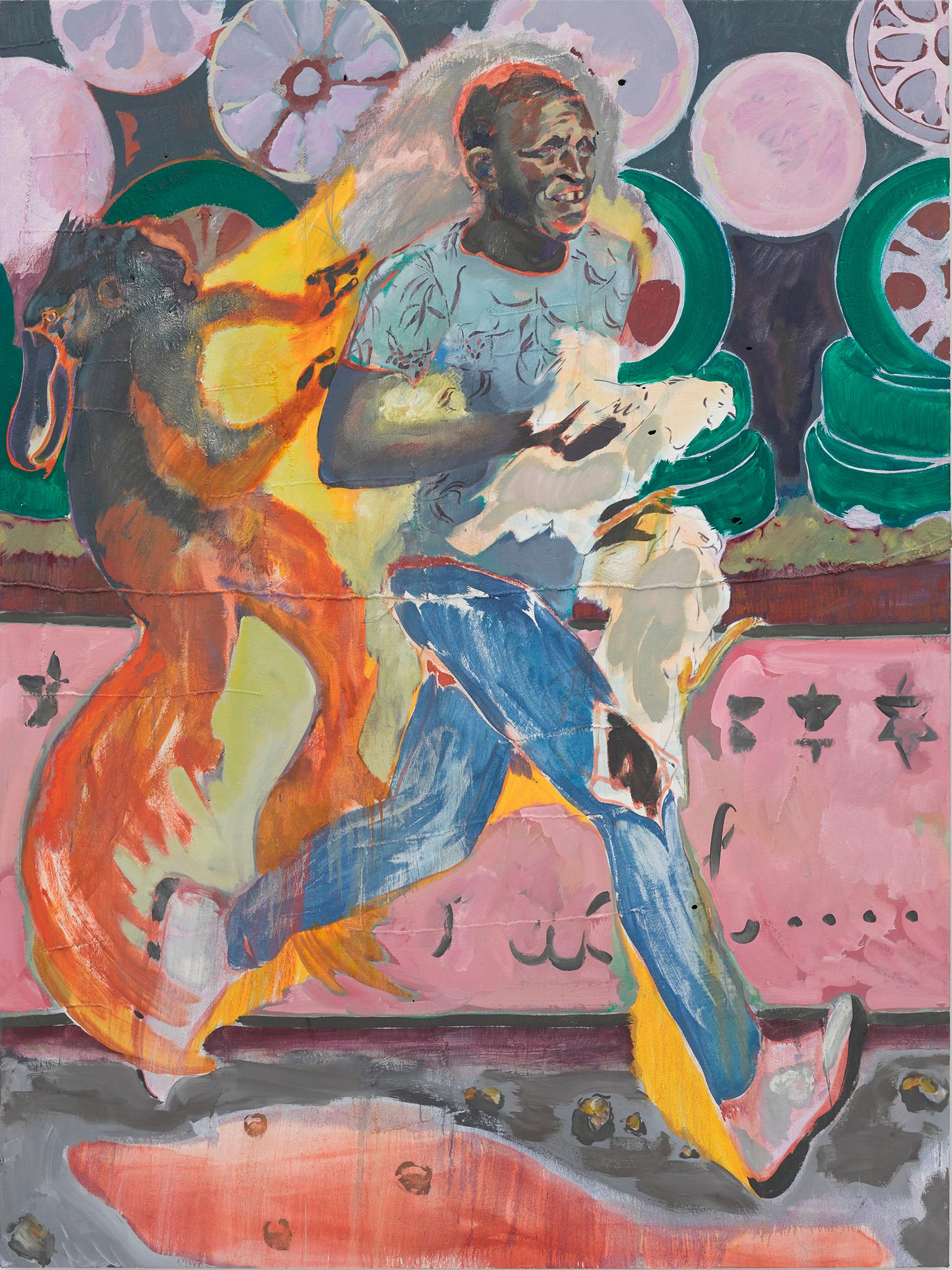

Michael Armitage: ‘Culture isn’t a single, well-defined line’

Kenyan-born artist Michael Armitage explains how his work relates to culture and the idea of exoticism.

Who is Michael Armitage?

Michael Armitage was born in 1984 in Nairobi and brought up in Kenya. He studied at Slade School of Fine Art and Royal Academy Schools, in London. His mother is from the Kikuyu tribe in Kenya and his father is a Yorkshireman. His paintings on traditional Ugandan lubugo bark cloth, which combine depictions of contemporary Kenyan political events with references to Western art history, seek to ‘exoticise’ and ‘self-exoticise’.

Q: How does your work relate to culture and the idea of exoticism?

The idea of ‘exoticism’ has always been important for me. It isn’t as simple as thinking of somebody in Hawaii as having a string of flowers around their neck and a grass skirt. It is more a fundamental question of identity, from the outside and from within.

Growing up, the exotic place for me wasn’t Kenya, it was London and the UK. I consider Kikuyu culture to be my own, but it’s also not as straightforward as that, because, even within Kikuyu culture, there have been so many shifts in the past 100 years – from the earlier tribal rituals and ways of defining oneself, to the presence of Christianity and the effect of colonial influence. My great-grandfather was one of the first – if not the first – convert to Christianity, and he was quite key in setting up the African Inland Church, which, for a long time, was the biggest church in the region. So, my predecessors didn’t practise any tribal ceremonies.

It was important for me to take on the idea of playing the role of ‘the other’, but also to look at someone else as ‘the other’. That’s where I am coming from with the idea of self-exoticism: the pressure to perform a culture that is considered to be authentic in some way, to perform it in the way that tourism asks you to perform it, means there is a level of dumbing down, of parody.

Culture isn’t a single, well-defined line. By its nature, it’s an amalgamation of many different things. Look at the masters of Western painting. One of the great Spanish painters is Greek – El Greco. One of the great French painters is Spanish – Picasso. And all the Americans are Europeans from different places.

I’m not someone who believes that, because you’re from a certain place, you’re not allowed to do or talk about things from other places. I don’t buy that for a second.

My wife is Indonesian, and when I first started going to Indonesia, I found it extraordinary how similar some of the Kenyan tribal customs are to what they practise there. It has a very different history of religion, and the customs take on very different aesthetic forms, but the similarity is uncanny. If you look at Kenya itself, and the different tribes that are considered to be quite opposing, they’re actually very similar, too. The things that define one versus the other are really quite subtle.

I feel we’re in a position where we should be recording the cultures that exist at the moment. Although customs are changing, culture is accumulative. I’m not someone who believes that, because you’re from a certain place, you’re not allowed to do or talk about things from other places. I don’t buy that for a second. To my mind, anything I see goes; anything I want to bring into a work, I can. If something made in Western Australia is useful for talking about an idea that comes from northern Kenya, citing a sculpture by a Spanish artist – all these things are just ways of making.

For example, in the Royal Academy show, I had a group of paintings based on the 2017 elections in Kenya. I very specifically set out to make them, and my preliminary drawings, a lot of the time, were just to pin down characters that would be useful. There are points where compositions from Western artists are also useful, because they refer to a specific well-known narrative.

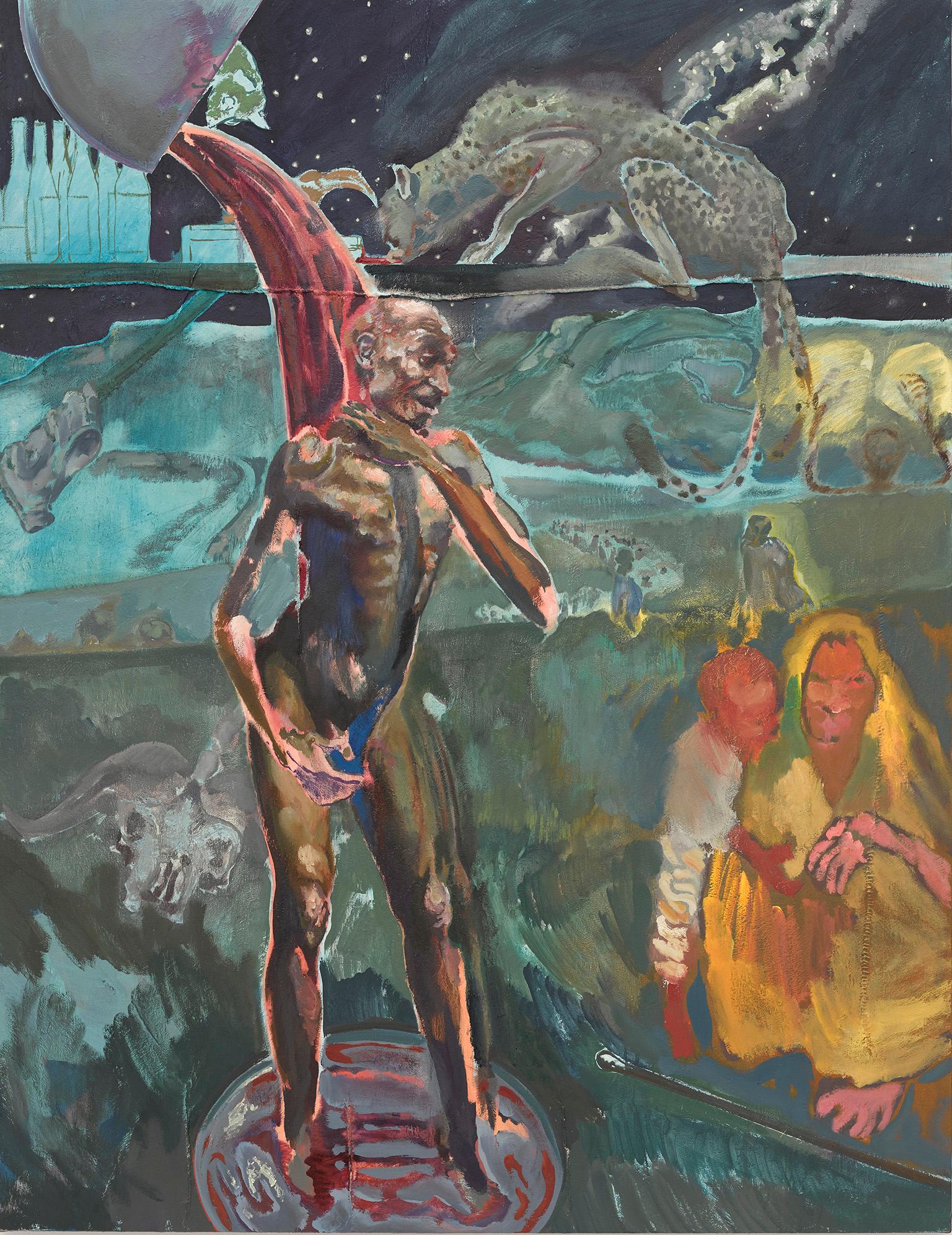

Pathos and the twilight of the idle (2019) was made referencing an altarpiece format, because I was thinking about these figures who were acting as supporters, but also as rabble-rousers for the political party I went to see. I looked at documentation of other rallies, which had turned violent, and these same guys were being shot at by police. I thought: ‘If one of these guys dies, he will be held up as martyr for his cause,’ but it’s such a dubious position, because they’re paid to cause trouble, and it’s hard to pin down anything particularly righteous about what they’re there to present or represent. So, I just wanted to riff off one of those figures with a Christ-like image of a martyr, because that’s something so familiar. I could have that within the painting, without having to be explicit and have my thoughts written down, rather simply inferred by the composition.

I don’t have a message. I’m interested in life, humanity and people. It would be great if my paintings were useful to others, but, beyond that, I wouldn’t want to dictate to anybody how they should consume them.

Interview by Anna McNay.

A version of this article first appeared in the spring 2021 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

‘Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict’ was on at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 22 May to 19 September 2021.