The pearlescent fables of Gustave Moreau

James Cahill tells the story of a series of extraordinary watercolours by 19th-century French artist Gustave Moreau, brought together in public for the first time in more than a century this summer at Waddesdon Manor.

A ‘fascinating oddity’ among the work of Gustave Moreau

In May 1914, a formidable collection of modern French art – that of the Marseilles art collector and connoisseur Antony Roux (1833-1913) – went under the hammer at Galerie Georges Petit, Paris. Featuring works by Eugène Delacroix, Auguste Rodin and Gustave Moreau (1826-98), Roux’s collection was a glorious snapshot of art at a turning point. The sale took place two months before the outbreak of the First World War, at the pivot between the ‘long 19th century’ and the birth of Modernism.

Moreau – one of Roux’s favourite artists – was himself something of a bridge figure, translating the mythological themes of neoclassicism into the strange, mercurial language of Symbolism. According to the catalogue of the 1914 sale, the crowning glory of Roux’s collection was a group of 64 watercolours created by Moreau between 1879 and 1885. These consisted of small, luminous vignettes based on the Fables of Jean de La Fontaine – a 17th-century anthology of cautionary and comedic tales. The catalogue claimed that, inspired by Roux’s commission, ‘the great artist produced this capital work, unique for its originality, its variety, its pictorial richness, its symbolic spontaneity and supreme expansiveness [envergure] of thought’.

Thanks perhaps to the strength of this sentiment, the group stayed together – it entered the collection of Miriam Alexandrine de Rothschild and has remained among the family ever since; but almost half of the works were lost in the 1940s through Nazi looting. This year, the 34 remaining watercolours will be shown at Waddesdon Manor, in the first public display of the series since 1906 – bringing to light a project that has usually afforded no more than a footnote in accounts of Moreau’s life and art.

Even in Moreau’s lifetime, the watercolours after La Fontaine were considered a fascinating oddity. British critics who saw them in London in 1886, after their initial showing in Paris, were baffled. ‘A lot of them pointed out how odd the commission was,’ remarks Juliet Carey, curator of the exhibition at Waddesdon. ‘They thought it was such an un-Moreau subject.’ Indeed, it was Roux, rather than Moreau, who had first conceived of a group of works inspired by La Fontaine. He began by commissioning multiple artists – Moreau among them – to respond to the Fables. At the resulting exhibition in Paris in 1881, Moreau’s contribution dazzled the critics and Roux invited him to take on the commission single-handedly. There followed a close creative dialogue between the men. ‘There are letters in the Moreau archive in Paris, indicating a touching correspondence between Moreau and Roux, where you can see the patron and the artist diplomatically expressing their ideas,’ Carey explains.

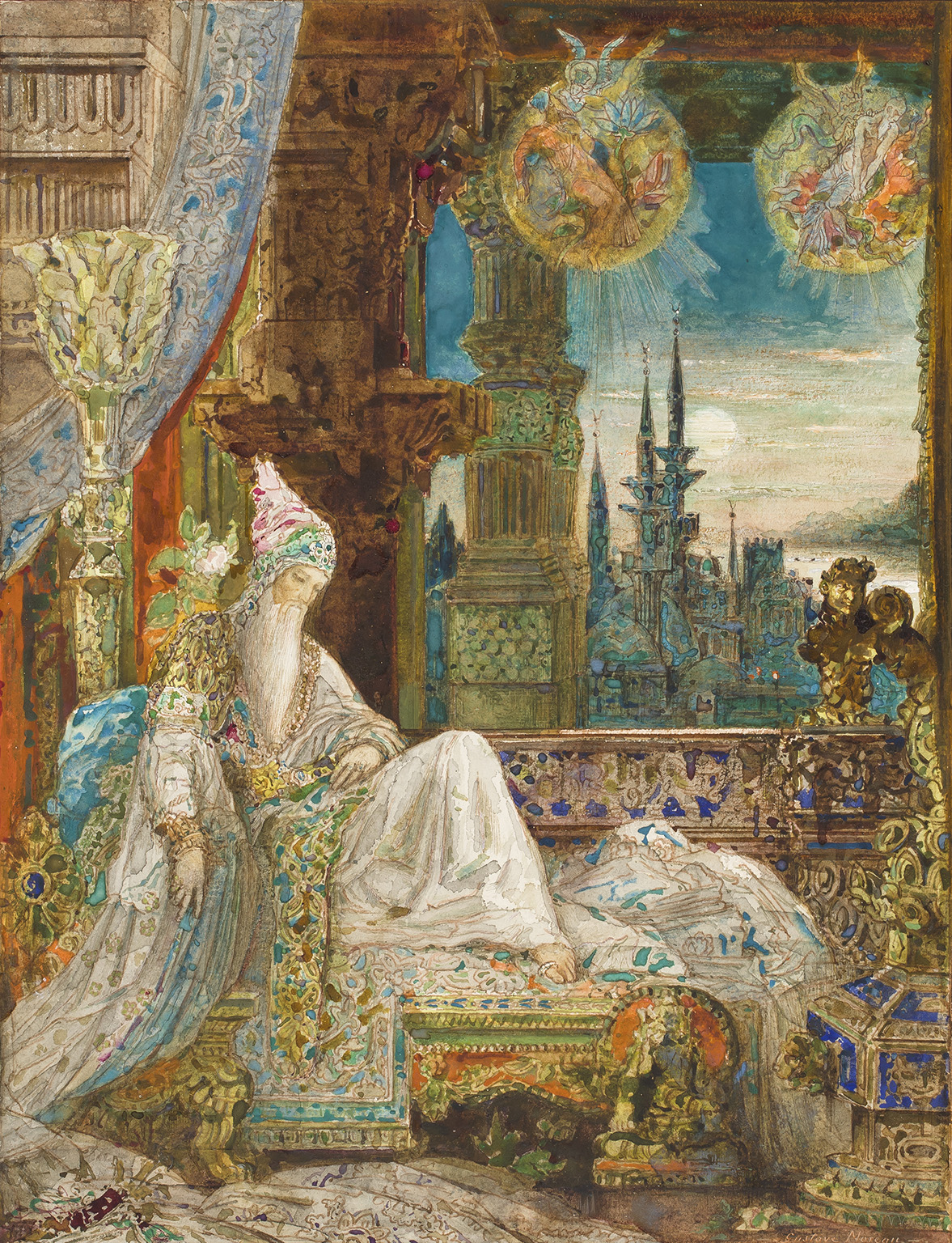

The dialogue that was enacted by Moreau’s watercolours was also a historical and literary one. La Fontaine’s collection of some 240 poems has been described as a stream of miniature comedies and dramas – episodic proverbs whose quixotic mood occasionally sharpens into satire. The overriding note, as La Fontaine himself suggested in the preface to the first collection, is that of la gaieté – ‘a certain charm … that can be given to any kind of subject, even the most serious’. This quality of blithe seriousness – reminiscent of fêtes galantes (the term used to describe Antoine Watteau’s paintings of idealised outdoor encounters and entertainments) – resurfaces and evolves in Moreau’s series, whether in a scene of a milkmaid whose daydreaming has led her to drop her pot of milk, or in a sensual reimagining of the ancient Indian story of a mouse transformed into a woman (a scene of metamorphosis that plays out within an Alhambra-style fantasy of gold and topaz).

Bringing forth new worlds from old myths

Undoubtedly, part of the appeal of the Fables for Moreau was their eclecticism. The myriad sources and subjects of the tales imbue them with a dual quality of gnomic familiarity and exotic otherworldliness – very often, the stories resemble tales from other times and traditions. In his first six books (published in 1668), La Fontaine drew extensively upon the fables of Aesop (the sixth-century BC Greek author whose name has become a synonym for proverbial wisdom – although his existence is itself something of a fable), together with other classical authors including Horace and – more obscurely – the fabulists Phaedrus and Babrius. The second collection (1678-79) focused more heavily on east Asian legends.

In several of his watercolours, Moreau embraced Greco-Roman themes of the kind that had long pervaded his work. Phoebus and Boreas portrays the sun god Apollo driving a pair of white steeds, his trailing blond hair echoed in the sweep of his turquoise gown. The story itself is left largely untold: La Fontaine recounts how Boreas, the north wind, and Apollo engaged in a competition to see which of them could uncloak a passing traveller; the wind blew violently to no avail, before the sun god gently warmed the man – inducing him to disrobe.

Other works address more homespun subjects. The Cat Transformed into a Woman shows an interior scene in which a naked woman crouches before a fleeing mouse. The setting could almost be the same soft-lit, tall-windowed interior imagined by Edward Burne-Jones in his depictions of the myth of Pygmalion from the 1870s. The story from La Fontaine derives from multiple stories – including the Panchatantra Sanskrit fables of ancient India – in which an animal is turned into a woman but retains her native instincts. Even as she crouches in the fullness of her human beauty, the sight of the scurrying mouse captivates her. As La Fontaine writes: ‘To work reform, do what you will,/ Old habit will be habit still.’

The Cock and the Pearl reimagines La Fontaine’s version of an episode in which a cock discovers a pearl while pecking for grain – transmuted into human characters. We see a beggarly man who has inherited a valuable manuscript, turning his property over to a bookseller in return for cash. The piquancy of Moreau’s depiction lies in the expressions of the two characters – the guileless visage of the peasant versus the prim, superior countenance of the bookseller, which captures something of the timeless snootiness of an upmarket merchant towards an artless client: think Julia Roberts in the film Pretty Woman, snubbed by the saleswomen of Beverly Hills.

The disparate and intersecting sources of the Fables chime with Moreau’s own oeuvre – a crucible of mythological, Biblical and romantic subjects that helped to forge the decadent sensibility of the late 19th century. The series after La Fontaine gave him an opportunity to elaborate upon this repertoire of themes, incorporating ‘exotic’ Orientalist material such as The Dream of an Inhabitant of Mongolia, known to us through Félix Bracquemond’s etching after the watercolour, in which a long-bearded man in sumptuous Chinese garb nods off within an opulent, stage-set-style interior worthy of Crystal Palace.

More than this, the fables of La Fontaine appear to have provided Moreau with the opportunity to create his own private mythosphere or mental otherworld. The pictures collectively evoke a realm of dreamlike apparitions, anthropomorphic animals, allegoric humans and transcendental – ever-changing – light. The act of translating a literary text into a sequence of pictures was, for Moreau (as for artists before him, such as Titian in his mythological poesie) an act of re-creation, rather than a straightforward illustration of familiar tales. ‘There’s a sense of Moreau really stretching himself and learning in these works, and being flexible,’ Carey says. ‘And yet they’re absolutely Moreau, and a lot of critics point that out – that they’re utterly Moreau and not really like La Fontaine: it’s not pithy and punchy and coarse.’

Painting with rubies, sapphires, emeralds and pearls

The distinctiveness of the group lies partly in the pearlescent colour – a quality that was noted by Charles Blanc, a critic for Paris newspaper Le Temps, who saw the series in 1885: ‘The watercolours for La Fontaine’s Fables render everything else pale. One imagines oneself to be in the presence of an inspired artist who might have been a jeweller before turning to painting – and who, having succumbed to the intoxicating power of colour, might have crushed rubies, sapphires, emeralds, topazes, pearls and mother-of-pearl to make a palette.’

The idiosyncrasy of the works lies, moreover, in their focus on animal characters. One group of preparatory drawings focuses on animals that Moreau observed in a Paris zoo (he had written to Roux complaining that he couldn’t paint animals unless they were akin to those Nicolas Poussin had painted). ‘He spent hours at the zoo, drawing,’ Carey says. ‘And the drawings are quite magnificent – a whole other side of his art that makes him look like he’s in a tradition of the Enlightenment investigator.’ Among the creatures he saw was the monkey who appears, in one watercolour, riding on a dolphin, both their bodies specked with iridescent blue.

The watercolours were a relatively late project by Moreau – he was 53 when he embarked on it, and at the height of his renown: in 1880, at the Paris Salon, he had shown his landmark paintings Galatea and Helen. Oedipus and the Sphinx, perhaps his most celebrated work – depicting the confrontation between Oedipus and the winged tormentor of Thebes – had been exhibited at the Salon of 1864. The exhibition at Waddesdon will throw light on a body of work that has long been eclipsed by these paradigms of his career, and on a more informal and picaresque mode than that of his grand mythologies. But it will also shift attention back onto the artist himself – as a figure who remains underrepresented in British collections, and who has lacked curatorial attention in recent decades, other than a touring retrospective in 1998. ‘A few years ago, I was at the Botticelli exhibition at the V&A,’ Carey recalls, ‘and one of the things that struck me was the number of people gathered around a beautiful Moreau painting in the room of 19th-century reflections of Botticelli. I realised how people don’t really know Moreau in Britain.’

Waddesdon Manor is an apt setting for this moment of reclamation. One of 40 Rothschild mansions built around the world in the 19th century, and the only one to retain its collections, Waddesdon Manor is – in its setting, architecture, décor and objects – a compression of epochs and styles: neo-Renaissance French chateau, English country house and (in recent years) sculpture park for contemporary works. The house’s ‘gilded and marble rooms’, in the phrase of its creator Ferdinand de Rothschild, offer a counterpart of kinds to the iridescent, fictive world of Moreau’s art. ‘The watercolours were made in the very years that Waddesdon was being built,’ Carey points out. ‘They are part of the contemporary world of Waddesdon, although they couldn’t be more different in some ways. There’s the element of 19th-century Frenchness, and yet Ferdinand didn’t collect avant-garde art.’

An entry on Moreau in the 1886 guide Le Petit Bottin des Lettres et des Arts described his watercolours as ‘exalting in the wild dream of perished civilisations’, and yet – as with Modernist art and poetry – the lure of the old was harnessed, in Moreau’s case, to the creation of mutable, fragmentary, interiorised voices. Something of the Janus perspective of Moreau’s art, its capacity to re-enliven the art of previous centuries with an evanescent modern (or proto-Modernist) gleam, was encapsulated by the artist and designer Charles Ricketts (1866-1931). Writing under the pseudonym Charles Stuart in the magazine The Dial in 1893, Ricketts expressed the view that Moreau’s work at its best looked ‘as if he had passed a sponge across the faded hues of some ancient picture, making it visible for the moment’.

The more you see, the more we do.

The National Art Pass lets you enjoy free entry to hundreds of museums, galleries and historic places across the UK, while raising money to support them.