© Douglas Gordon / Photos: © Glasgow Life 2014

© Douglas Gordon / Photos: © Glasgow Life 2014

© Douglas Gordon / Photos: © Glasgow Life 2014

© Douglas Gordon / Photos: © Glasgow Life 2014

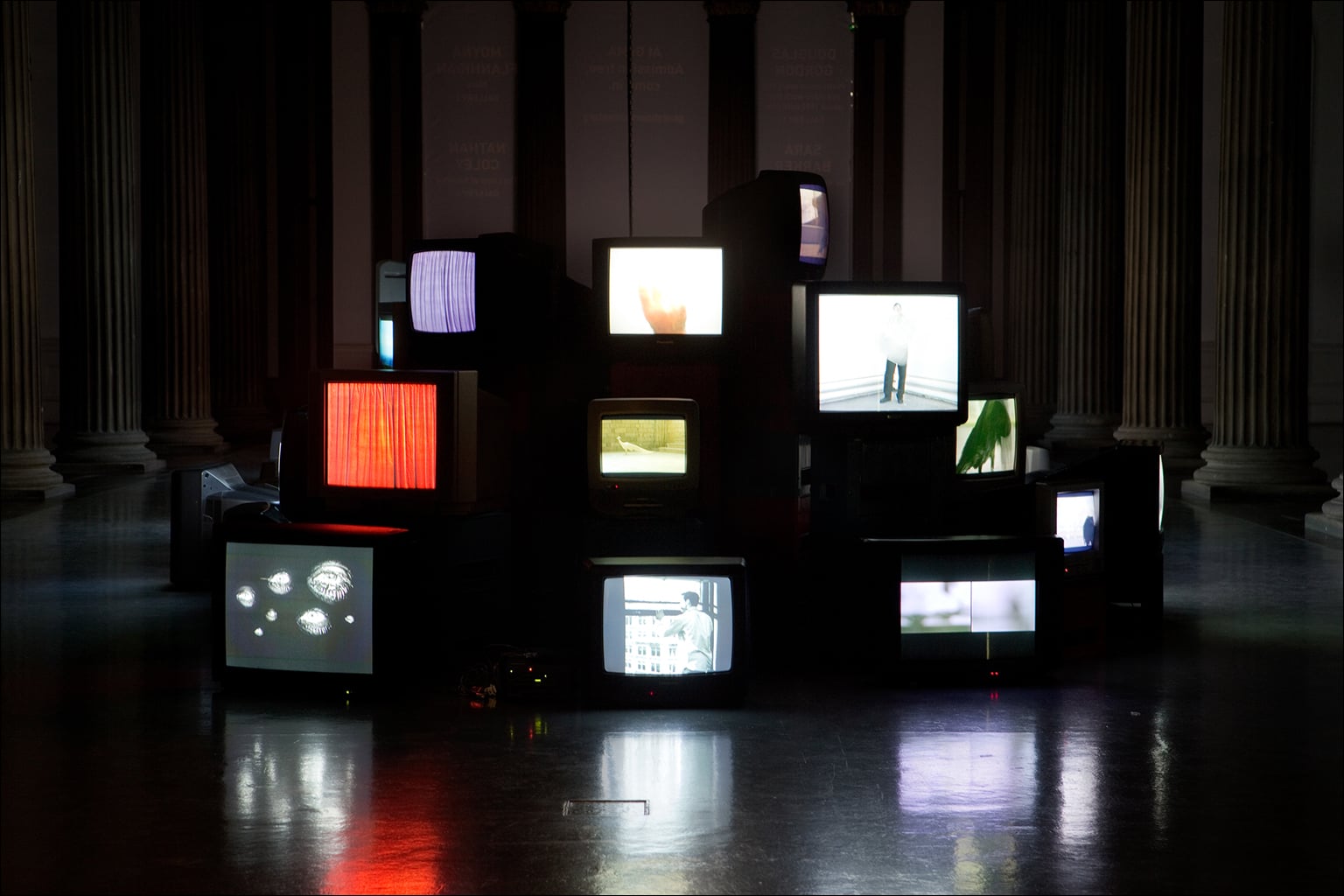

Pretty much every film and video work from 1992 until now

Douglas Gordon

- Art Funded

- 2015

- Dimensions

- Various dimensions and durations

- Vendor

- Gagosian Gallery

Douglas Gordon is the artist famous for slowing down Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, stretching its running time from 109 minutes to 24 hours (1,440 minutes), so transforming the thriller into a moving sculpture.

It is difficult to explain why, more than 20 years on, this seemed so exciting at the time. He may be Hollywood's creepiest-ever boy next door, but Norman Bates in slow-mo, gripping a dinner tray for 15 minutes, isn't chilling at all to watch. Back then, however, 24 Hour Psycho seemed anarchic. With monstrous temerity, Gordon had mangled a classic and got away with it. A similar fate befell Victor Fleming's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which Gordon slowed down for his work Confessions of a Justified Sinner in 1996, the year he won the Turner Prize. As much as the talk was about stretching time and the malleable nature of film as a sculptural medium, there was also a grudging respect for the nerve of the artist taking on such revered material. A double self-portrait made at the time depicts Gordon as an artist and a monster, hideously disfigured by sticky tape. In part, this was Gordon reflecting the paradoxical relationship he had with the movies, mutilating the very thing he professed to love. But the divided self, viewed through the prism of film noir, also became a dominant theme in his art, even after he stopped appropriating the medium for his own creations. Like any Hollywood miscreation ransacking Manhattan, Gordon's tyrannous reign over film died out when humanity caught up with him. Digital technology and YouTube made it possible for us all to be Douglas Gordons. Born in Glasgow in 1966, Gordon studied at Glasgow School of Art in the mid-1980s, where he became associated with a tight-knit group of artists, among them Roddy Buchanan, Christine Borland and Martin Boyce. With the YBAs in the ascendancy, this hard-core gang of Glasgow natives refused to bow to the inevitable and move south. Gordon's Turner Prize win in 1996 cemented their reputation as a reckoning force and paved the way for many younger artists in Scotland. Pretty Much Every Film and Video Work From About 1992 Until Now. To Be Seen on Monitors, Some with Headphones, Others Run Silently, And All Simultaneously, 1992 – in progress is the self-explanatory title of an archival sculpture by Gordon that has been acquired for Glasgow City's Art Collection with the help of the Art Fund. It consists of 82 film and video works displayed on old television screens. The archive will continue to grow, with each new film or video installation Gordon makes being added to it. The decision to present each new work on the old-fashioned CRT (cathode-ray tube) television may at first appear perverse. This technology is increasingly obsolete, and Gordon has had to provide the collection with 100 CRT televisions for future use. In many ways it is a historical document of a time when viewing was a more state-controlled pastime, yet there is also an appealing retro-aesthetic to this glowing memory bank. Think sci-fi movies of the 1960s in which computers are the size of Cadillacs and operated by white-coated brainiacs. Ultimately, Pretty Much… is a one-stop shop to the artist's obsessions and anxieties. He has a saturnine eye for the gothic; although he lives in Berlin, his art still inhabits a world where the struggle between good and evil is fought in the Calvinistic environs of predestination. Whether it is the battle between James Stewart's voice and Bernard Herrmann's film score in Hitchcock's Vertigo or his smaller-scale videos in which the artist turns against himself, wrestling his own arm, Gordon's art is haunted by opposing forces. It is also noticeable how many of his later films feature animals, in particular the uncannily beautiful 2003 Play Dead, which features an elephant in a gallery. Perhaps the oddest aspect of Gordon's art, however, is how unobtrusive the technology is. For all the stretching and cutting-up of film – in a similar manner to early modernists who cut up paper for collages – his early works never seemed particularly technical. He can now command Hollywood budgets, yet the art, for all its sophisticated technical detail, retains that simplicity of intention. What we are haunted by is the psychological struggle of good versus evil, as narrated by Robert Louis Stevenson or James Hogg, and the uncanny sense that somewhere there is a ghost in the machine.

This work was acquired with assistance from the Wolfson Foundation.

Provenance

The artist.