How artists have responded to our watery world

A series of exhibitions is highlighting the vital role water plays in the health of our planet, and the urgent need to manage and protect it.

A version of this article first appeared in the summer 2025 issue of Art Quarterly, the membership magazine of Art Fund.

The question of how water originated on Earth has puzzled scientists for centuries. Some suggest it arrived from asteroids, while others attribute its presence to water-rich minerals that melted during the planet’s formation. Whatever its source, life certainly couldn’t exist without it.

Covering approximately 70 per cent of Earth, the oceans are our planet’s lifeblood, regulating climate, producing oxygen and providing food. Yet, as a result of human activities, their health is increasingly threatened as overfishing, acidification and rising temperatures endanger marine life and coastal communities.

Freshwater resources are also being severely compromised as pollution, overexploitation and climate change cause shortages, flooding and health problems across the world. While the planet’s oceans, seas and waterways have been an enduring source of inspiration for artists across the ages, the alarming decline of these precious ecosystems has prompted a growing body of contemporary artistic responses, highlighting the need for innovative and sustainable solutions.

Oceans in jeopardy

This summer, the Sainsbury Centre continues its series of ‘Big Question’ seasons by posing the question ‘Can the Seas Survive Us?’ Three thought-provoking exhibitions address our shared relationship with the seas, our planet and each other, including ‘A World of Water’, which examines the current challenges facing the world’s oceans.

‘The impact of global climate change on our oceans is one of today’s most fundamental questions,’ says director Jago Cooper. ‘Sea-level rise, ocean deoxygenation, plastic pollution, large parts of Norfolk falling into the North Sea – these are issues that concern us all.’

Taking East Anglia’s deep maritime connections to Europe’s Low Countries as its starting point, the exhibition traces shifting artistic responses to the sea, from romanticised seascapes to reflections on environmental breakdown. As part of his research, curator John Kenneth Paranada led a team of scientists, artists and activists on a two-day walk from the Sainsbury Centre along the Wherryman’s Way to Great Yarmouth.

‘According to data published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, much of Norfolk’s coastal landscape will be underwater by the year 2100,’ he says. ‘We wanted people to see for themselves what could be lost if action isn’t taken.’

The team also took a 36-hour sea voyage from Lowestoft to Rotterdam aboard a 1921 fishing smack, witnessing firsthand the effects of sea-level rise and energy industrialisation, from oil rigs to wind farms. ‘This is a show about environmental crisis, adaptation and resilience building,’ explains Paranada. ‘It amplifies lived experiences of climate realities, not as a distant future, but as a crisis already unfolding.’

A selection of antique maps and books highlights the close historic ties between East Anglia and the Dutch coast, revealing how maritime trade and cultural exchange shaped these region’s economies and shared heritage. This is explored further by a salon-style display pairing Dutch Golden Age seascapes with early-19th-century works by the Norwich School of Painters.

‘The cross-pollination of visual languages between England and the Netherlands created a new type of imagery,’ says Paranada. ‘English artists such as John Crome and Robert Ladbrooke developed a vernacular style as they depicted the sea’s vast and sublime nature.’

Today, the need for scientific exchange between these two regions has never been more urgent. ‘Both are facing massive sea-level rise,’ says Cooper. ‘But, unlike Britain, the Netherlands has developed world-leading flood defences and climate adaptation strategies. They have a totally different approach to us, despite the fact that our coastlines are eroding faster than almost anywhere in Europe.’

Since 1880, average global sea levels have risen by more than 23 centimetres, and the rate is accelerating. Addressing the issue head on is Dutch artist Boris Maas, whose towering chair sculpture The Urge To Sit Dry (2018) raises the sitter above a flood line based on Nasa’s predictions of sea levels rising by a staggering 65 centimetres by the year 2100.

‘This piece is amazingly urgent because much of the Netherlands is already below sea level,’ says Paranada. ‘A version sits in the office of the Dutch Minister for the Environment, reminding politicians to think about new solutions to climate change.’

The sea’s destructive power is registered in Maggi Hambling’s dynamic series Walls of Water (2010-ongoing). Inspired by mighty waves smashing into a Suffolk seawall near her studio, these semi-abstract paintings point to the threatening realities of a changing climate. Elsewhere, the devastating effects of coastal erosion are addressed by Julian Perry’s small, double-sided canvases of decaying East Anglian sea defences.

‘All of our seas and oceans are interconnected,’ says Paranada. ‘What happens in the Pacific or Atlantic eventually ripples back to the North Sea. My hope is that this exhibition will stimulate collective action for the seas and that audiences will want to be a part of the change.’

Alongside ‘A World of Water’ is work by Sāmoan-Japanese artist Yuki Kihara, including her critically acclaimed photographic exhibition ‘Paradise Camp’ – created with members of Sāmoa’s third-gender Fa’afafine community – and the exhibition ‘Sea Inside’, featuring work by contemporary artists including Evan Ifekoya and Hiroshi Sugimoto, which further explores our more intimate relationships with our seas.

Wonder beneath the waves

‘We should all be concerned about the state of the ocean,’ says James Russell, curator of the show ‘Undersea’ at Hastings Contemporary. ‘It’s obviously in crisis, but it’s also important that we don’t lose our sense of wonder towards it.’ To that end, he has brought together a delightful selection of works depicting the sea and its inhabitants through the ages and across cultures, from anonymous 18th-century illustrations, to Surrealist-inspired paintings by British Modernist Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949), and contemporary pieces by Michael Armitage and Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists. ‘This is a celebration of the oceans as a shared cultural space,’ he explains.

The oceans are home to abundant marine life, plenty of which ends up on dinner plates. Lobster and crab have been eaten since prehistoric times and feature in fine paintings by Oskar Kokoschka, Edward Bawden and Charles Collins, whose Lobster on a Delft Dish (1738) depicts the cooked crustacean on a piece of blue-and-white delftware, which offsets its bright-red shell. Octopus is a part of many food traditions, and traditional Japanese female divers, or ‘ama’, have caught them off Japan’s coasts for centuries.

‘These women have an important place in Japanese culture,’ Russell explains. ‘They are renowned for diving without breathing equipment and are admired for their courage and endurance.’ One of these remarkable divers is portrayed in Taiso Yoshitoshi’s dramatic woodcut A Woman Abalone Diver Wrestling with an Octopus (c1870). ‘Yoshitoshi was a popular printmaker – the last in a great line that included the celebrated Hokusai,’ says Russell. ‘Scenes of violent conflict were his speciality, and here he shows an ama battling a giant octopus.’

Folklore, myths and legends relating to the seas are as old as humanity itself, and another grouping of works considers sirens and mermaids. In Paul Delvaux’s dreamlike painting A Siren in Full Moonlight (1940), the hybrid creature reclines amid classical buildings, her pearly skin bathed in milky light. In Greek mythology, these deadly beauties enchanted sailors with seductive songs, luring them onto the rocks. But Delvaux’s temptress appears more like a mermaid than the traditional depiction of a siren as half-bird, half-female.

Mermaids are also the focus of paintings by Klodin Erb, whose 27-strong series Mermaids (2023) shows the mythical sea-dwellers frolicking with fish, sitting on rocks, and casting spells on unsuspecting humans. Presenting a harmonious aquatic community, these delicate canvases are a joyful appeal for the conservation of marine ecosystems.

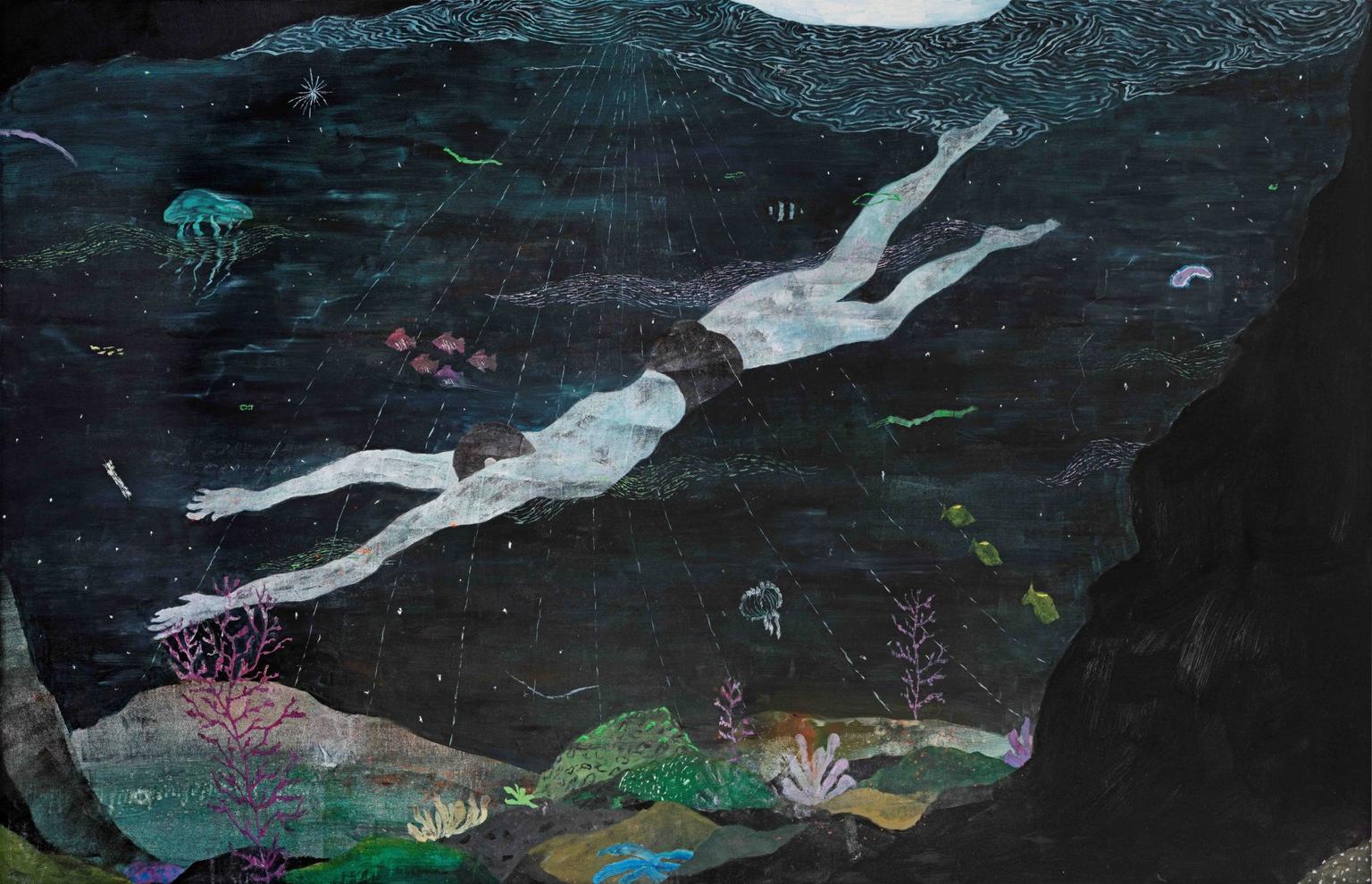

Whereas Erb relies on imagination, the Greek painter Yiannis Maniatakos (1935-2017) donned diving gear to paint his haunting views of the seabed directly from observation. Typically spending up to five hours per dive, he painted on waterproof canvases and weighted himself to the seafloor as he captured marinescapes around the Cycladic island of Tinos. Untitled (2000) shows a sandy seabed lit with sunbeams disappearing into a murky cloud of blue-black water. The scene is eerily devoid of life, unlike Tom Anholt’s painting Deep Dive (2022), in which a figure descends into the depths surrounded by different marine creatures.

Not a drop to drink

Despite the Earth’s surface being more than 70 per cent water-covered, freshwater is surprisingly rare, making up just three per cent of all water on Earth. Of this, around 69 per cent is frozen in glaciers and the ice caps, with another 30 per cent hidden as groundwater. This leaves just one per cent readily available for human use. The vital place of freshwater access is explored at the Wellcome Collection in ‘Thirst: In Search of Freshwater’, which examines the environmental, social and cultural importance of this precious resource.

‘The seas and oceans might capture people’s imaginations but our lives literally depend on freshwater,’ says curator Janice Li. ‘Thirst’ opens with a cuneiform tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh (c1900-1600bce), an ancient Sumerian poem that includes an account of the first war fought over water access.

‘In early civilisations, the demarcation of territory was closely linked to the presence of water, and many conflicts have been about access to freshwater,’ explains Li. Elsewhere, a new commission by Raqs Media Collective explores the thirst for water in the face of its volatile and unpredictable nature. Thirst/Trishna (2025) is a rich multi-channel video installation in which the lavishly ornamented stepwells of Rajasthan, India, become a conduit to address the present-day problems of climate change and water management in the region.

An intriguing collection of Roman water pipes discovered by Li in the Wellcome’s collection spotlights the sophisticated water systems that were implemented across the Roman Empire, though a 19th-century map showing the distribution of cholera in London is a stark reminder of the dire consequences of poor sanitation.

Elsewhere, a newly commissioned installation by Karan Shrestha explores how glacial melting and ineffective infrastructures in Nepal have combined to cause fatal flooding and landslides, contributing to the ongoing epidemic of the viral disease dengue. ‘Shrestha is indigenous to the Kathmandu valley and a lot of his works involve collaborating with local communities,’ explains Li. ‘This work tells the untold stories of those who have experienced flooding and disease; people and places you rarely, if ever, hear about in our news cycle.’

Today, safe drinking water is too often taken for granted, but a lack of access to clean water remains a source of poor health for many. Mineral Lick (2019) is a large textile hanging by Lebanese artist Dala Nasser, which evidences the toxicity of tap water in Beirut. It was made by soaking fabric in tap-water samples from across the city, into which equal amounts of rock salt and dye were added. The different acidity levels in the water caused salts to grow, or not, on the material accordingly, in shimmering shades of rusty brown and yellowish green that appeared both beautiful and threatening.

While a lack of freshwater poses significant risks to health, so too does its overabundance, especially when displaced onto land through flooding.South African artist Gideon Mendel spent 17 years documenting the human impact of floods around the world. His video installation Deluge (2007-24) draws on a vast archive of footage taken in 11 different countries, showcasing the resilience of individuals affected by devastating floodwaters. ‘It’s really moving to see so many destroyed homes,’ says Li. ‘Despite the socioeconomic disparity between locations, the human emotions, losses and vulnerability are felt universally.’

At Tate St Ives, Emma Critchley’s immersive video and sound installation Soundings (2024) employs underwater filming and choreography to draw attention to the effects of deep-sea mining. Part of this is a letter co-written with Indigenous Pacific activists, scientist and others, titled Rights of the Deep, which calls for the change needed in our hierarchical relationship with our deep oceans, in order to protect them.

Water, as these exhibitions demonstrate, is a dynamic force, never content to stay still. Shifting between solid, liquid and gas, its transformative power continuously reshapes the Earth, and artists across the world will continue to make work inspired by and in response to it. As the challenges of ocean protection, sustainable development and responsible water management grow ever more acute, the question of what must change in order to protect our environments and secure the future of our entangled seas and water resources will onlybecome increasingly urgent.

Visiting list

‘Can the Seas Survive Us?’, Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, featuring ‘A World of Water’ and ‘Darwin in Paradise Camp: Yuki Kihara’, to 3 August; ‘Sea Inside’, 7 June to 26 October. Pay if and what you can.

‘Undersea’, Hastings Contemporary, to 14 September. 50% off entry with National Art Pass.

‘Thirst: In Search of Freshwater’, Wellcome Collection, London, 26 June to 1 February 2026. Free to all, 10% off in shop and café with National Art Pass.

‘Emma Critchley: Soundings’, Tate St Ives, to 21 September. 50% off entry with National Art Pass.