Bobby Baker and Eileen Cooper on art and motherhood

Appearing together in two group shows of women artists, Bobby Baker and Eileen Cooper discuss feminism, art school and the influence of parenthood on their work.

A version of this article first appeared in the spring 2024 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

Who are Bobby Baker and Eileen Cooper?

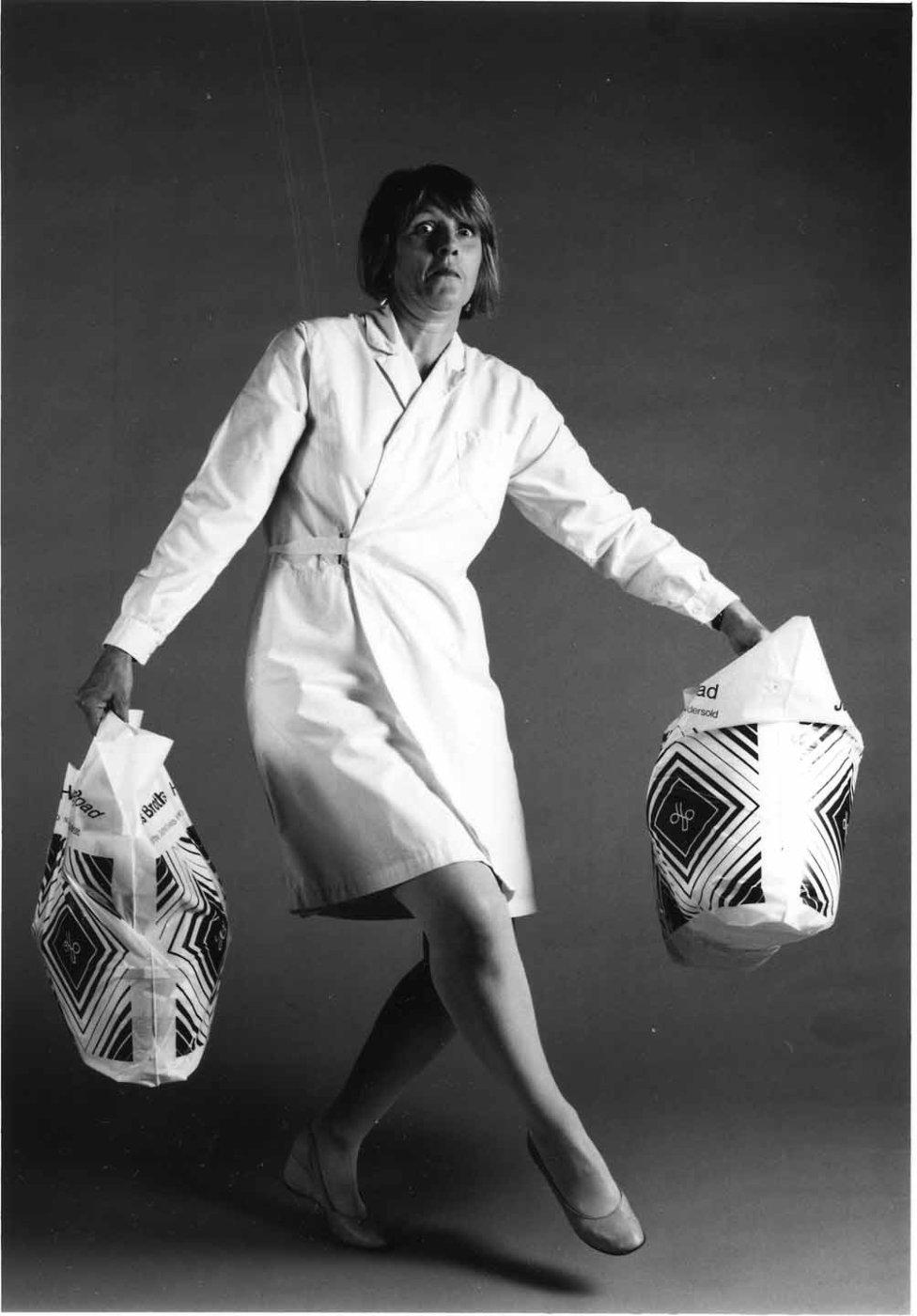

Bobby Baker was born in 1950 in Kent. Through darkly funny performances such as Drawing on a Mother’s Experience (1988) she has exposed undervalued aspects of women’s labour, and taboos surrounding both physical and mental ill health. Her icing-covered installation An Edible Family in a Mobile Home (1976) featured a cake family in the iced interior of a prefab and has been reconstructed for Tate Britain’s current exhibition ‘Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990’.

Eileen Cooper was born in Derbyshire in 1953. As a painter and printmaker, her work has largely been dedicated to the human figure, often exploring autobiographical subject matter through allegory and myth. She has taught at St Martin’s, the Royal College of Art and the Royal Academy of Arts. She was elected a Royal Academician in 2000, and from 2010-17 served as Keeper of the Royal Academy – the first woman to hold that role. Like Baker, her work features in both ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’, at Arnolfini in Bristol, and ‘Women in Revolt!’.

Hettie Judah: You each have two children – what impact did motherhood have on you initially as artists?

Bobby Baker: I didn’t think I wanted children because I knew the problems it would pose, but then I longed for a baby. In 1980 my career was booming: after I was in the 1979 ‘Hayward Annual’ exhibition, I was selected for ‘About Time: Video, Performance and Installation by 21 Women Artists’ at the ICA. Then Dora was born, and I immediately felt like a bad smell when I went into an art space. I brought her to an artist meeting before the ICA exhibition, and apart from Susan Hiller, who was friendly and kind, everybody looked away. There was a sense of shock. Babies felt taboo. Even though My Cooking Competes (1980) [a performance delving into autobiography through food preparation] for ‘About Time’ was successful, I lost my sense of entitlement to be an artist.

Privately, I did a year of timed drawings when Dora was five and Charlie two, some of which are in ‘Acts of Creation’, but it took eight years to make public work again. That was the performance Drawing on a Mother’s Experience (1988). Motherhood had a huge impact. But it didn’t stop me working in the long term.

Eileen Cooper: I encountered negativity as well, but nothing like that. I was teaching at St Martin’s School of Art when I found myself pregnant. Male colleagues patronisingly told me that it was ‘very brave’ to have a baby at that point in my career. Luckily, I was with a gallery, Blondes Fine Art, and had a deadline for a show, which was a great driver. We moved from our council flat into our first house, and I set up a home studio. It felt very positive.

The most shocking thing was the response of a critic who’d always been supportive. When I showed the new paintings it was as though the work had suddenly gone from being radically feminist to being linked to the idea of ‘2.5 children’ and conservative Thatcherite values, which horrified me. However, my work that focused on giving birth and the transformation of having children was welcomed by collectors. My career took off – the Arts Council and British Council both acquired my work. I’m thrilled that the painting Putting Down Roots (1985) in ‘Acts of Creation’ is from this period.

BB: I also felt my radical friends judged me as selling out. Because I’d lost my confidence in the visual art world I entered a showcase for the National Review of Live Art. I rehearsed Drawing on a Mother’s Experience the night before, alone in my husband’s [Andrew Whittuck] studio. Performing it the next day I realised how out of place I was. I was older, I’d taken a packed lunch – and I was sitting there thinking, ‘Oh my god, I’ve got tomato sandwiches. I hope nobody notices!’

The work of caring for young children is hugely important – the foundation of a healthy society – and I was outraged that it had no status. Drawing on a Mother’s Experience was about that. The show was a sensation and blasted me into that performance art world.

EC: I’d like to talk about the positives as well – through becoming a mother, I learned so much about using my time. I did my thinking before I got in the studio, so I could get straight to work when the baby was napping. I wore gloves and overalls that I could whip off to breastfeed.

BB: During those eight years I worked with Andrew as a food photography stylist, and in the commercial sector collaborated with people with different skills. On set for an expensive advert, I thought: ‘I want to be the performer in front of the camera, and the writer, and the director.’

EC: That sounds as if it was formative for how you developed your working methods. Your practice was so ahead of its time. Was it hard for you to call yourself an artist?

BB: As a student, I really wanted to go to the Royal College of Art. They kept turning me down, which affected my confidence. I was thrilled by my work in the 1970s. And I met performance artists like Shirley Cameron, whose work is also in ‘Women In Revolt!’. Working in art centres and other spaces, rather than galleries, was more democratic.

EC: I started studying at Goldsmiths in 1971. There were no female staff in my first year. I was aware that at St Martin’s there was this real force – Gillian Ayres – and felt the women students there were lucky to have her. I was excluded from the male group who sat around thoughtfully discussing serious things. And I think this did me a favour – I was liberated from that.

BB: I admired Gillian Ayres. She was glamorous and flamboyant. She and her husband Henry Mundy were the arty crowd. They were always drinking and gossiping around Vice-Principal Frederick Gore’s office. She never taught me but I knew she was there, which must have affected me. St Martin’s was rather anarchic. The guy who was meant to be running First Year had fallen down the stairs, so there was no one in charge. I was decidedly lost, but it was so much better than being at home.

EC: When I went to the Royal College women were not taken very seriously in the painting department. I was quite shy. RB Kitaj was doing a drawing class, and Peter de Francia, who was head of the course, said, ‘You must go and talk to Kitaj. He’ll be so interested.’ Of course, Kitaj didn’t want to talk to me, and I was too intimidated to even begin the conversation.

BB: I remember the fear that somebody would tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘You’re a nice middle-class girl from Sidcup. You can’t be an artist.’

EC: At Goldsmiths, I’d had several wonderful male tutors including Bert Irvin and Basil Beattie. Bert made a point of finding women artists: ‘Have you looked at Käthe Kollwitz? At Paula Modersohn-Becker?’ They must have been aware of shifting values. And then this word ‘feminism’ appeared.

BB: I didn’t know about that until later, in my twenties. At art school I had fun, but when it came to my work, by my third year I’d been written off. I made good paintings but I wanted to do my dissertation about chocolate mousse. I was thinking about so many things, but no one understood.

EC: They just wanted you to be a painter, probably. Teaching kept me connected to my peers. At the Royal College, I taught with Helen Chadwick, who was a brilliant inspiration, so clever and provocative. Once I became a mother I didn’t go to private views because they were always at 6pm, when you’re up to your ears in childcare. People like Helen being around was enough for me.

BB: I took Drawing on a Mother’s Experience to the National Review of Live Art in Glasgow and saw fabulous work. The Wooster Group were there with the incredible [American actor] Ron Vawter. For the NRLA’s 10th anniversary I wore a cake with live candles on my head and covered myself in buns. When Vawter picked a bun off me I thought I would collapse. It was exciting, but I felt grief that I was cut off from the visual art world.

The real problem was money. Andrew and I were both self-employed. We almost went bankrupt. That’s why I cracked up in the end, trying to keep it all together. And the culture in the 1990s was misogynistic, even amongst some women. I braced myself for that with ‘Women in Revolt!’, but it’s been a joy. I’m excited by the work, the atmosphere and the dialogue around it. I think we’re at a real turning point with these shows.

EC: I love the way the context is represented: the women’s movement, gay liberation, the politics of it all, it’s very rich. I’m thrilled to be with people whose work I’ve always loved, like Helen Chadwick, Alexis Hunter and Sonia Boyce. There are many people who were wiped out of art history. This is their time now.

BB: The early history of the feminist movement was not all rosy, there was a lot of backbiting, yet the Postal Art Event, and Shirley Cameron performing in her rabbit hutch [dressed as a Playboy Bunny], was all going on. And I was out there dressing up as a meringue! The first time I sensed I was part of something bigger was in ‘About Time’. I could suddenly see a whole body of work by other people and thought: ‘I’m part of a movement.’

EC: My equivalent experience was ‘Women’s Images of Men’ – another of the three all-female shows at the ICA in 1980. I answered an open call in Time Out magazine. When my work was accepted I met the organisers: Catherine Elwes, who is in ‘Women in Revolt!’ and ‘Acts of Creation’, Pat Whiteread and Jacqueline Morreau. The large-scale drawing that’s in ‘Women in Revolt!’ was in ‘Women’s Images of Men’. I still own it.

Although I was exhibiting a lot then, few things sold. It was my motherhood paintings that captured people’s imaginations. Work, life and teaching all need different experience and ability, but they feed each other. Towards the end of my teaching career, I became the first female Keeper of the Royal Academy, an all-engrossing role. Being Keeper was an opportunity to develop myself – to be decisive and supportive. It was a learning curve to discover I had that in me. I was using skills I learned as a mother.

BB: As a mother you become superbly skilled at running things. I’m fascinated that being Keeper made you see your own work with more confidence.

EC: Yes. After six years I resigned because I’d got into a headspace where I could ask myself what I really wanted. Which was to see my work in more public collections. So I approached curator Kathleen Soriano. We put together a three-year plan and are now in our fourth. During that time, she curated my exhibition at Leicester Museum. It’s helping me grow my legacy, whatever that will be. You do think about what you’re going to leave behind you. I’m very obsessed by death.

BB: Because my dad died suddenly when I was young, I’m accepting of death. I was fortunate to work with Andrew, who’s a brilliant photographer, and Routledge published a book about my work. I received some money from the Arts Council to be able to include 200 colour illustrations. We also made nine DVDs and a small website.

At the launch of this ‘Bumper Package’ in 2008, I’d just had breast cancer. I had no hair but was ecstatically full of life, and I did a performance called First F.E.A.T [a celebratory work featuring ladle dancing] with 11 students. It was the most sensationally funny, exultant show. Putting the book together and digitising my work was pivotal.

EC: Another thing that strikes a chord is your relationship with Andrew. My husband, Malcolm, is a graphic designer, so I’ve always had really excellent publications plus his constant support. When I was 60 we produced a beautiful book and have made a couple of others since. We were able to have full control: I went to collectors and pre-sold copies of the book with an original print. I’ve become alive to the possibility that you can do ambitious things and be entrepreneurial.

BB: I set up Daily Life Ltd. in 1995 to produce my work – it’s now an Arts Council National Portfolio Organisation. When I was 60, I saw the gulf in recognition with my male peers. Daily Life Ltd. has a great board of trustees, so we recruited brilliant curators and a senior producer, and raised the money to rebuild An Edible Family in a Mobile Home for ‘Women In Revolt!’. It’s been thrilling. Having it on the forecourt of Tate Britain, you start to get noticed. Young people want to see this work as well as our generation. I think you have to keep shaking at the gates, don’t you?

‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’, Arnolfini, Bristol, 9 March to 2 June. Free to all, 10% off in shop with National Art Pass.

‘Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990’, supported by an Art Fund Jonathan Ruffer curatorial grant (see the autumn 2023 issue of Art Quarterly), continues at Tate Britain, London, to 7 April. 50% off paid exhibitions National Art Pass.

A writer, curator – most recently of ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’, a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition – and co-founder of the Art Working Parents Alliance.